Every time we tweet, retweet, write a blog post, or publish an article about the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, we become unwilling combatants in a decades long war that, if we’re being honest with ourselves, we know very little about. The so-called ‘frozen conflict’ (a cleverly configured yet analytically useless oxymoron if there ever was one) is less about the contested territory that spawned it, and more about deflecting attention away from two illiberal regimes that have grown disparagingly repressive and inattentive to the needs of their people. In this sense, the attention we give it, void any meaningful details about the conditions on the front, or developments leading to its resolution, end up boosting, in one way or another, these regime’s efforts to one-up each other in the world of social media and world opinion.

Both the Azerbaijani and Armenian governments have spent enormous sums on building up their armed forces, while their economies have grown increasingly fragile, and their populations despondent about the status quo. Azerbaijan has squandered more than $20 billion on defense spending over the last decade. By some accounts, its annual spending is greater than Armenia’s entire state budget. Meanwhile, Armenia has been forced to accept Russian military assistance and military bases on their territory in order to keep up with their neighbor in the vain hope that a Russian presence will act as a deterrent. Each side is locked into a dangerous and illusory game that spending more, or acquiring the latest technology, will give them the edge over the other. It won’t.

The corollary to this misbelief in the power of technology to bring ultimate victory is that any time something happens on the front line, one side or the other tries to prove its technological advantage by sheepishly parading their war-prizes in front of state media and other foghorns of the regime. Suddenly – what matters on the front is not the conditions of the soldiers (which are deplorable), the useless and constant waste of human life, or the 1984-esque endless nature of the conflict – but that a helicopter was shot down, a drone was captured, that this many tanks were destroyed, that many casualties inflicted. Endless body counts. Tallies dutifully kept by the secretaries of war.

In Nagorno-Karabakh, this particular type of Technowar (a term popularized by James Gibson in his seminal work The Perfect War) is blended with peculiar mix of hyper-active social media ‘watchers,’ mostly living abroad (including myself), and local restrictions on freedom of press – including the jailing and violent beating of journalists. Lacking important details from the front, we reporters and researchers from afar end up becoming unwilling combatants in a war that pits body count vs body count, downed helicopter vs. downed helicopter, one-by-one. Day-by-day. We become the secretaries. The tally keepers.

In a war that has no instigator, where determining who started what is a fruitless endeavor, where facts are hard to come by, where escalation is calculated to score political points, not to bring battlefield gains, each article that we write ends up being used in a propaganda campaign waged by either side on the terrain of world opinion.

The war has become the single most valuable and abundant source of fuel for each regimes’ propaganda machine. Every night the local media notches daily tallies from the front, or reports on some new weapon acquisition that will tilt the battlefield in their favor. The constant media barrage is meant to create a sense of national duty and patriotism, while deflecting attention from the issues that matter most to daily life – lack of access to good jobs, basic services, and a deteriorating economic situation that is going to get worse before it gets better.

All the while, the soldiers who are sent to fight and die in the trenches are mostly neglected and the horrors they encounter there are unceremoniously swept under the rug. Even the relatively high number of non-combat deaths, including a deplorable rate of soldier suicides, becomes subjected to geopolitical manipulation in order to portray one side as somehow weaker than the other. Opposing state censored (read: controlled) press release details of their enemy’s soldier suicides and poor morale but rarely discuss their own.

Ironically, the constant media barrage is matched by a near media blackout when it comes to access for investigative journalists – meaning we know very little about what actually happens on the front lines, other than what can be corroborated by both sides. What’s left ends up being technocratic details put out by state-officials that bear little resemblance to the actual contours of war. Perhaps this is one reason why researchers are so quick to turn to the ‘frozen conflict’ narrative even though thousands have died fighting since the 1994 negotiated ceasefire.

We researchers, reporters, and journalists, need to be careful not to feed the propaganda machine. But this is easier said than done.

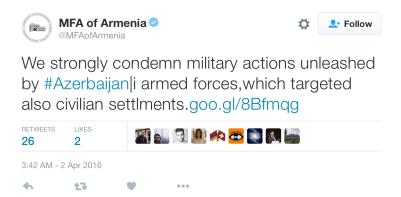

When the conflict escalates (itself an outcome of the incessant logic of one-upmanship) the temptation is to post our thoughts in rapid succession, and share what little information we have. However, because both sides keep information close to their chests, and deny access to journalists, the only thing that media outlets have to go on is opposing side’s propaganda. This amounts to reporting on inflated body counts, what types of weapons were used and where, and other such nonsense that only fuels the machine. In other words, the media develops a strange obsession with the types of helicopters (Mi24/35), or ThunderB drones, or tanks destroyed, or number of casualties, because it’s otherwise starved of real details about the situation on the ground. But it’s these very technical and abstract details that the logic of technowar depends on.

#Azerbaijani Mi 24/35 was downed in Eastern part of #Mrav Mountain #NKpeace https://t.co/VcCoAo0E7S pic.twitter.com/r0NvJBG5kh

— Armenpress News Eng (@armenpress) April 2, 2016

Given the amount of misinformation and downright lies propagated to boost support for one side or the other, most of our collective efforts end up acting as an echo chamber for the powers-at-be. It’s not helpful that it’s hard to denounce both sides equally in 140 characters or less – or that the #NKpeace hashtag (the one meant to be promoting resolution) can be so easily and unceremoniously taken over by propagandists on either side. The result is that even when we carefully avoid wading into the waters of misinformation, we none-the-less often reward propagandists and their surrogates.

#Karabakh army holds good protection, destroyed #Azerbaijan heavy armament, incl 4 tanks, 2 helicopters, 2 drones. pic.twitter.com/3F4vn3ti3G

— Karabakh MOD (@Karabakh_MoD) April 2, 2016

Well-meaning people get sucked into the lingua-franca of technowar and unknowingly drift into meaningless debates about minor details that say little about the root causes of the conflict or the reasons why it persists. We resign ourselves its logic, without thoroughly investigating its contradictions. For example, how the very mediators of the conflict are the ones who benefit the most from selling weapons to both sides. Mediators that are themselves deeply embroiled in their own geopolitical game of cat-and-mouse. We write academic papers on the nature of ‘frozen conflict’ but know little about frozen trenchfoot that soldiers endure. We can recite statistics endlessly, scrutinize the same maps over and over, but not much else. And this is exactly how both regimes would prefer to keep it.

Armenians starting a #KarabakhNow hashtag on Twitter. Won’t be long before Azerbaijanis counter. And thus the war goes online… #NKPeace

— Onnik J. Krikorian (@onewmphoto) April 2, 2016

—-

An unfortunate example:

Breakdown of #Armenia and #Azerbaijan military forces and equipment #KarabakhNow pic.twitter.com/POdIXWmymK

— Donnacha Ó Beacháin (@Donnachakaz) April 3, 2016

Ryan McCarrel is a PhD Candidate in Geopolitics at University College Dublin. He has lived and researched extensively in the Caucasus. You can follow him on twitter @ryanmccarrel

Photo by Yana Amelina/Wikimedia Commons

*Article updated Sunday April 3rd 2016.

A really thorough article. My only feedback here is that the author does not analyze the regime differences. Both countries are undeniably corrupt but one of them, Azerbaijan, has an authoritarian regime (as oppposed to oligarchy/democratic kleptocract in armenia). Hence, activists in azerbaijan that are involved with anti-war effforts get imprisoned or receive death threats (or die) or those abroad with families in AZ fear persecution of their families.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Hasmik, please do more research about this, activists in Azerbaijan get imprisoned because of other reasons and never because of their anti-war efforts.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Though you are right in pointing out that the war has evolved into a legitimacy battlefront, where the survival of each government in both Baku and Yerevan is based on its performance in the NK struggle, you don’t quite mention how ingrained and personal the conflict is to every citizen of the respective countries (particularly in the mass participation nation-states we live in today). There are reasons why so many mothers and fathers still enthusiastically accept the mandatory military service of their children and volunteer in the droves. This is one of the few conflict that if you removed all political and state structures, the people on the ground would fight as they do now.

The shortest way to ‘solve’ this conflict is relinquishing territorial claims, both by Armenians (on Eastern Anatolia, Nakhichevan and leftover bits of NKAO) and by the Azeris on the NK area altogether, including occupied territory. No, ‘justice’ will not be served, but it will force both governments to stop politicizing the issue of “the right of return” of the refugees, who in the Azerbaijani case were deliberately kept impoverished (and many still are) to shore up claims on territories. Everyone involved knows that, but can’t admit to it because of risk of losing legitimacy. Territorial transfers are off the table for over a decade, and only those well-dressed white people in suits keep regurgitating this utter non-sense that neither side will accept. Likewise anyone ‘out there’ claiming this has no military solution at least ought to remember that the actors on the ground think otherwise. Days when the people in charge and those fighting each other were former neighbours/colleagues/friends is long gone. The prism of perception of the ‘other’ is through ethno-nationalist textbooks and militaristic terms you describe. The elites, so to speak, have swallowed their own lies.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on The Armenian Observer Blog.

LikeLike

“We write academic papers on the nature of ‘frozen conflict’ but know little about frozen trenchfoot that soldiers endure.”

Brilliant!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Foreign Intrigue.

LikeLike

Good article, thank you. I’ve been saying this for years, but no one listens as people wants sensations crap. I’ve been to NKA 15 or so times as well as other non recognized republics like Abkhazia, Transnistria etc and after many discussions you come to realize that only people want to continue this a geo political players and arms dealers. Common men, and young conscripts just suffer more

LikeLike