I came to Morocco for two reasons: one, to escape the long Irish winter; and two, to take photographs. Travel and photography have become important components of my life – both as a hobby and increasingly as a lifestyle. But from an ethical standpoint, both are deeply problematic.

Travel is always an ethical question. The very fact that I, as a privileged white man from the United States, am able to freely move about the world as I please, whereas others (including many of my friends) are bound to place by oppressive visa regimes, poverty, and travel restrictions, means that ‘travel’ for pleasure’s sake carries with it the dilemma of inequality and repression. Wars of aggression fought by the United States along with its allies in the Middle East, Central Asia, across the Sahel and Maghreb and elsewhere, have sent refugees fleeing from conflicts, while the globalization of capital on the Global North’s terms, has imprisoned half the world’s population on starvation wages pressuring many millions more into economic migration. Both have only added to the growing disparity between those who can ‘travel’ and those who can’t, as governments try to regulate the movement of people (but not capital) in order to satisfy narrow political and economic goals.

So while some are forced to risk their lives braving the mediterranean on leaky boats – and many thousands have drowned trying – I can fly for less than a night out in Dublin to a ‘faraway land’ to explore an ‘enchanting’ culture and be whisked away by tour guides to geological marvels of the earth. Truth be told, the difference between a plane and a sinking boat is simply a designation that privilege affords – often, a privilege ascribed by birth and affluence rather than merit or need.

But look deeper and ‘Travel’ as the privileged like myself understand it carries with it further ethical conundrums – from environmental devastation to cultural emaciation. It’s the latter I want to focus on here, as it intersects with my other interest – photography.

(Taken in a village near Zagora, Morocco – March 2016)

(Taken in a village near Zagora, Morocco – March 2016)

Travel is a child born from curiosity. This is not inherently a bad thing. Curiosity in diversity can provide an intellectual spark for progressive thought – especially when it is sincere. It can open the mind to the world and humble the individual. But more often than not, curiosity is imbued with a set of pre-existing assumptions – or expectations – about what a place should look like, of what I am looking to find there, and how I will feel like while ‘experiencing’ the place that I intend to go. These assumptions are not born on their own. They are a product of a long history of interaction between the global north and south – a division of ‘appropriate’ roles that we are assigned by virtue of our skin color, passport, language, sex, and place of origin. When curiosity and travel come together, I become the privileged visitor, and ‘they’, the visited.

Much has been written on this before. The most famous being Edward Said, who’s book Orientalism, was published in 1978. In it, he wrote:

“The Orient that appears in Orientalism, then, is a system of representations framed by a whole set of forces that brought the Orient into Western learning, Western consciousness, and later, Western empire…. The Orient is the stage on which the whole East is confined. On this stage will appear the figures whose role it is to represent the larger whole from which they emenate. The Orient then seems to be, not an unlimited extension beyond the familiar European world, but rather a closed field, a theatrical stage affixed to Europe.”

It is this theatrical stage that we yearn for when we dream of the sands of the Sahara, of riding a camel into the sunset, and of waking in the morning to sip an aromatic mint tea cultivated somewhere in a nearby desert oasis. But the theater is a co-construction. First, in the global north’s collective imagination, and second, in the market created by this imagination that tour companies and travel agencies (both local and foreign) pander to in order to sell tickets to the performance. No where, has this been so clear to me as in Morocco. And here I find that I’m both a member of the audience, and a producer.

(Taken while on a tour of the Sahara near Merzouga, Morocco – March 2016)

Morocco has a very different photographic culture. ‘Street photography’ is not common as a result – or at least, more frowned upon as an intrusion. Women cover their faces when a tourist passes with a camera at the ready. It is polite to ask people before taking a photograph even when they are not the focal point, and all too common to be turned down or asked for a bit of money in return. When you ask why, people quite rightly say that they don’t want to be on a postcard or plastered all over some tour company’s website without compensation. In this way, lenses are directed to the stage to photograph the performance – and so with every exposure we become producers of the play – even if we’d like to document something more representative of every day life.

(I asked if I could photograph this man’s TV shop in the Medina of Fès. He kindly agreed, but quickly covered his face – Morocco, 2016).

(I asked if I could photograph this man’s TV shop in the Medina of Fès. He kindly agreed, but quickly covered his face – Morocco, 2016).

As a result, women and children are virtually erased from the picture altogether. As is everything that doesn’t conform to the Orientalist image that already existed in our imagination prior to arrival. In my photos you’ll find people wearing traditional garb, and working in traditional crafts or trading artisanal goods that could have just as easily been made in a factory in China as in a workshop around the corner from my hostel. It’s not important where they were made, but that they are sold in the Medina, to the passersby who imagine with little difficulty that everything is ‘authentic.’ While you’ll find photos of donkeys and chickens, of sand dunes and old mud brick hovels, you might not see the Toyotas and brand new apartment buildings, or men in suits and women wearing ‘European’ style clothing – much less the plastic bags and Coca Cola bottles that litter the landscape.

I worry, that because this Orientalist image is associated with a certain ‘primitiveness’ (a product of our imagination and an outcome of poverty left in the wake of colonialism and caused by the enclosure of capitalism more-so than anything special to the local culture), that my photos will reinforce this narrative when it’s not at all how I understand Morocco or how I’d like it to be understood. In fact, I think this only adds weight to some of the ridiculous arguments being made by xenophobes and nationalists in Europe and the US.

On the one hand, then, because I am restricted from photographing some things while encouraged to photograph ‘touristy’ stuff, I am actively cultivating the Oriental image of Morocco. On the other hand, I question whether part of this image, which is partially upheld locally by local guides, local tour companies, and local photographic preferences, is somehow designed to protect those who live here from the constant intrusion of the traveler.

Morocco’s economy is virtually dependent on tourism – something that is reinforced by the orientalist image that sends tourists to every corner of the country in search of camels and ancient medinas. But although they may be forced to sell an Oriental version of themselves to the tourists to make a living, they can still protect part of their life from intrusion by diverting the tourist’s attention to the stage. I find myself conflicted over whether this is a good thing – but also recognize that it is not my choice nor should it be.

Not all of my photos have been completely restricted. I’ve had a few opportunities to speak with a local tanner, and some local kids, and of course people working at the hotel as waiters and cleaners.

One of the more interesting people I had a chance to speak with was a young adolescent on the road to Merzouga. He told me about how the Tuareg and Berber lifestyle had been destroyed by colonialism and the construction of borders across the Sahara where there used to be none. Their nomadic lifestyles have largely become a distant memory and a source of nostalgia that you can get a sense of in the lyrics of their songs. They recreate this lifestyle for tourists visiting the desert to ride camels and camp overnight. But I can’t help but feel that it only prolongs the sense of disenfranchisement from what at one time was rightfully theirs – an open desert free to cross and trade -a lifestyle that is now the closed off to them by border guards, but open to me and my privilege as a tourist.

Unfortunately, I can’t photograph that.

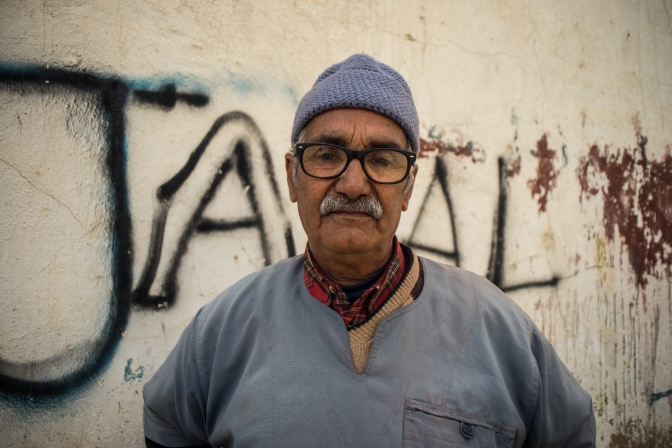

(A Tanner from Fès. He was one of the few people who agreed to let me take their portrait. I met him while he was drying some leather hides on the hills outside the Medina – March 2016).

Update: This photo and article will be featured in DeFactory’s forthcoming Atlas of Humanity project based in Desenzano del Garda, Italy.

Interesting article. I also reflect a lot on the consequences of tourism while travelling. I studied about Orientalism in my university and got more sensitive about the way locals “portray” their homes and lifestyle for wealthy tourists. It is actually not only common in far away places. I live in a very touristy city in Germany and can see the same effects there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Before writing this I had a long conversation with an Italian who was on the same tour as me. She was telling me about how her town has been transformed, so that local artisans and markets have been replaced by little stands selling kitsch tourist collectibles, like refrigerator magnets and snowballs. The overall effect is that her town’s no longer that great a place for the locals, as everything is pandered to out-of-towners. The thing I took away from our conversation, is that I’m not sure that we’ve really figured out how to adapt to mass tourism – and particularly, to preserve ‘the authentic’ experience that so many seem to crave… (I want to write about the ‘Authentic’ in another blog post soon, so I’ll leave that for later). Anyways, mass tourism is a fairly recent phenomenon that we don’t have much experience with. The difference between Orientalism and mass tourism, is the way in which Orientalism is an exchange or product of the Occidental (Western Europe) imaginary. This is an asymmetric exchange.

LikeLike